The Cutthroat Battle for Controlling Le Monde

What’s going on at Le Monde? Is its independence in peril? Probably not. But the current confrontation might radically change the ownership structure of France’s flagship paper.

This version has been updated and corrected on Monday, Sept 16.

1. The latest

On September 10, Le Monde’s newsroom exposed the conflict with its shareholders, more specifically with a troublemaker named Daniel Kretinsky. In an op-ed, 460 journalists expressed their concerns. Excerpts:

For the first time in its history, it could be forced to admit a new shareholder in its capital without its journalists being consulted. Our editorial freedom is at stake. (…) In October 2018 we learned the sale of 49 % of the shares belonging to Matthieu Pigasse to the industrialist, Daniel Kretinsky. Le Monde’s Independency Group, a minority shareholder gathering the association of journalists, the staff, the readers and the founders, was not informed of this operation. (…) Last summer, our concern increased with the opening of exclusive negotiations by Mr. Pigasse and Mr. Kretinsky to buy the shares of the Spanish group, Prisa, another non-controlling shareholder of Le Monde. (…) On Tuesday 3rd September, the Independency Group, therefore, requested that Xavier Niel and Matthieu Pigasse fulfilled their promise to guarantee our independence and to sign this right of approval before September 17th. Xavier Niel did so on Monday, September 9th.

On Friday, 500 celebrities and intellectuals followed up in another Op-Ed.

2. Le Monde’s current ownership now

The ownership structure of Le Monde goes back to 2010 when the paper narrowly avoided bankruptcy and was saved by a €110 million investment made by Xavier Niel (a telecom entrepreneur), Pierre Bergé (former owner of Saint Laurent), and Mathieu Pigasse (a Lazard partner). The pipework consists of three cascading entities, which look like this:

Note that this structure does not reflect voting rights or balance of power within the board of directors. Under the shareholders' agreement, a 25% block of shares called Pôle d’indépendance (Independence Group) is non-transferable and provides staff with certain key rights.

Once taking into account all of the Russian dolls, the final ownership of the media assets looks like this:

3. The dreaded evolution feared by the newsroom and by Xavier Niel

In 2017, Pierre Bergé died of old age. His inheritors are not fond of owning a newspaper on which they have no control and that also faces the uncertainties of the sector.

Last year, Matthieu Pigasse, for all sorts of reasons explained below, decided to sell to the Czech industrialist Daniel Kretinsky 49% of its holding in entity #1, le Nouveau Monde. The billionaire wants to extend the current media assets he currently owns in the Czech Republic to France.

The move altered the balance:

Prisa, the Spanish group that owns El Pais, is also willing to sell (the Madrid daily is not doing well). Kretinsky is interested, and since the Czech businessman paid top dollars (actually euros) for Pigasse’s stake, Niel is hesitant to enter into a bidding war.

UPDATE Monday, Sept 16, 17:00 GMT. In a previous version of this article, I stated that the Pigasse+Kretinsky duo could end up with a majority of 55% of Le Monde’s shares. It’s a mistake: before his death, Pierre Bergé said that his stake in Le Monde should be split evenly between the two other partners.

The worst-case scenario for Xavier Niel, therefore, looks slightly better: in the event of a sale of Prisa to his pair of rivals, Niel will end up with 30% and 45% for Pigasse+Kretinsky:

The soot operator remains in a pivotal position. He might try to impose new management or at least to have a seat on the board.

Hence the drama and the movie stars and writers stating how much Le Monde is essential to their daily routine. OK.

4. Who is Daniel Kretinsky and why doesn’t Le Monde want him?

For a newspaper who is in love with Greta Thunberg, Daniel Kretinsky looks like a Texan oil wildcatter crashing at a Greenpeace party.

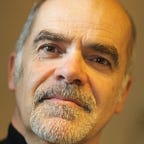

Daniel Kretinsky (pronounced Shre-tinski), 44, made a fortune in fossil fuels, more specifically by acquiring for cheap a string of coal-fired plants in Central Europe. Today, he owns 94% of EPH (Energetický a průmyslový Holding). His net worth is just shy of €3 billion. He bets that the plants will deliver inexpensive electricity to European countries that increasingly loathe nuclear energy. He also holds a stake of 4.63% in the retail chain Casino.

The perspective of being controlled by a coal mogul from Central Europe is not appealing for Le Monde’s 500 journalists, who, like in every Western newsroom, are beefing up climate change coverage. They can feel the soot already.

And there is Xavier Niel’s murky game.

5. Xavier Niel’s style

Xavier Niel, 52, is a telecom mogul who made a fortune overhauling the cell phone and ISP sector with inexpensive and aggressively marketed packages. He created a large cohort of cult-like followers. His net worth is estimated at $3.8 billion by Forbes. He is also the creator of “Station F”, the largest and most spectacular incubator in the world by under one roof (soon to be supplemented by a large real estate development). In addition, Niel funded “Ecole 42”, an innovative anti-elite school that churns out amazing and socially diverse computer geeks.

Incidentally, Niel is the son-in-law of Bernard Arnault, the luxury magnate and now the second world’s biggest fortune (net worth: $107 billion) after Jeff Bezos. Always eager to shine vis-à-vis the icy Arnault, Niel was used to boasting than he was approving the front page of Le Monde every-single-day. Except that he didn’t. Arnault realized that when Le Monde ran a series of unpleasant stories about him. (The owner of LVMH is not reputed for his unabated sense of humor, but rather for his sense of details: a couple of times, he summoned to LVMH headquarters, Avenue Montaigne in Paris, the editor of an inoffensive beauty magazine part of Les Echos Groupe he owns. Holding a ruler, in his sub-zero tone, he expressed his discontent that some photographs showcasing the group’s competitors items were a few centimeters larger than for LVMH’s stuff).

Xavier Niel also loves media. In his own way. About journalists, he once said: “When journalists piss me off, I buy a stake in their paper, and they leave me alone”. The quote had become viral. Niel said it was a joke of course. Still. His 2010 takeover of Le Monde was ruthless. His compulsive cost-cutting, 1–800-EAT-SHIT bumper sticker-like culture, collided with decades of lax management at the paper. (He got a hunch one day while negotiating the deal, he was about to hail a cab, when three different execs offered him a ride in their company car).

By leading the triumvirate of shareholders, Niel saved Le Monde when it was on the verge of bankruptcy. Does Groupe Le Monde make money? The newspaper is suffering from the devastated advertising market. Last year, profit came mostly from the sale of a large piece of land where the printing plant used to stand. The cashflow is helped by the legion of suppliers still suicidal enough to work with Le Monde; most of which are cruising at a rate of one-year payments delays on average. That’s Niel way. Media reporters in France usually avoid digging too deep; they joyfully put out the glowing narrative: digital subscriptions skyrocketing, etc. But so are the churn (huge) and acquisition costs. No one knows the truth about Le Monde’s P&L.

6. Unfortunately for Le Monde, Xavier Niel is not Jeff Bezos

When Jeff Bezos acquired the Washington Post for $250 million in 2013, he assigned three priorities: editorial excellence, technology, and client. Do your job well and I will do mine as the owner. He kept Marty Baron as the iconic editor and gave Shailesh Prakash, head of technology, an expanded role and all the resources needed to hire “A-people”, in Bezos’ parlance. Prakash was VP of engineering at Sears until 2011 when he joined the Post. He and Bezos speak quite often about the company’s developments. The CEO of Amazon trusts him so much that he made him an advisor to his space company Blue Origin. In addition to empowering internal talent, Bezos gave money to the Post: about $300 million.

No such thing at Le Monde.

Nine years after the acquisition by the Niel-led triumvirate, Le Monde is a penny-pinching company that has yet to undertake a decisive modernization. It is editorially fine but is technologically backward at every stage. The structure of its website is antiquated (by today’s standards), it is served by an arduous search engine (provided by Qwant, a French brand, that sells itself as an anti-Google). It is unable to process adequately the most mundane query, or power a decent recommendation engine, not to mention personalization. And while the Financial Times has created a subscription war-machine, Le Monde still requires a registered mail to cancel a digital (or print) subscription.

Fact is: Xavier Niel didn’t inject money in the company, except for questionable acquisitions like the likely soon-to-fold weekly L’Obs. (Niel is also building a huge new headquarter for the group’s properties, but it is mainly a real estate operation).

Niel has been enjoying the influence and prestige that goes with his partial ownership of Le Monde. His relationship with the French, old-fashion banking establishment changed overnight starting in 2010. It helped a lot.

Wisely enough, he refrained from influencing or criticizing Le Monde’s newsroom, allowing negative pieces to be published on his business. Not all owners do the same in France. He knows he has too much to lose by clashing with the newsroom. His main company, Iliad, which controls the mobile carrier and ISP Free is in trouble. Since its last peak in May 2017, Iliad lost 67% of its market value and clearly falls behind its competitor and bandwidth supplier Orange:

Three reasons: one, Illiad-Free is engaged in a price war with the rest of the ISP and cell phone players; two, Free Mobile’s service is terrible, and despite low prices, subscribers are hemorrhaging. Three, some European subsidiaries don’t perform well.

7. Niel doesn’t have the upper hand anymore

Of the original trio, Xavier Niel was by far the wealthiest. Pierre Bergé died a year ago, and his heirs and assigns are willing to sell.

As for Mathieu Pigasse, the agitated Lazard rainmaker has two issues: one, he is deeply frustrated at having failed to become France’s Finance Minister (nearly a done deal when Dominique Strauss-Kahn was still politically alive) and later, the Macron train left the station without him. More importantly, Pigasse is heavily indebted (he is said to have borrowed money from Niel for the 2010 takeover).

8. Niel’s original scenario disrupted

Since the beginning, Xavier Niel had always thought that, eventually, the stake owned by Pierre Bergé and Mathieu Pigasse, would fall on his hands like two ripe fruits. He once confided: “They simply don’t have enough cash. One day, we all will have to reinvest. They won’t be able to to do it. And I will buy their stakes”.

That was the plan until the coal-fired plant guy showed up.

Daniel Kretinsky paid top dollars for buying out Mathieu Pigasse: about €50 million euros. In theory, the operation would value Le Monde at €500 million, but given the shareholders’ agreement, special rights for the staff, and other provisions, it could be closer to €300 million.

10. Does this shift threaten Le Monde’s editorial freedom?

The short answer is no. At least not in the short term.

Even if the montage outlined above becomes a reality, a shareholder controlling the board does not entail a say on the newsroom’s management. In fact, the shareholders’ agreement signed in 2010, stipulates that the Directeur de la Redaction (the editor of the paper) must be approved the newsroom through a vote. This rarely guarantees a first-class candidate, but it is a proven protective precaution. That is not the case for the CEO and other key execs of Groupe Le Monde. But in the short term, there is no threat. Daniel Kretinsky himself has repeatedly said that he would respect the newsroom’s independence. This kind of statement is not worth much, but from a pragmatic perspective, the energy magnate has no interest to fight the newsroom. The indirect windfall will be much sweeter.

— frederic.filloux@mondaynote.com